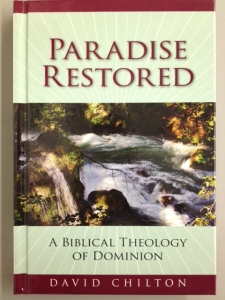

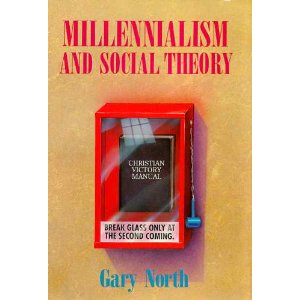

Here is an essay that Gary North says offers an accurate assessment of the origins and development of the Christian Reconstruction movement and its theological (and political) principles.

It was written in 2007 by a Ph.D. candidate at Ohio State University, Michael J. McVicar (posted in his blog, June 2012). Neither a “hit piece” nor a ringing endorsement. But, I am warning you! It paints a rather stark (yet relatively bias-free, though it’s a little prickly towards the Tyler, Texas side of the ledger) picture of the major players — Rousas J. Rushdoony and Gary North — as well as other key figures who helped shape and define the movement, how it came into being, how it ultimately came to split into disparate camps, and how the movement, in McVicar’s opinion, fares “today” (2007).

Now, this is not a “decline and fall” kind of an article. It is more of an academic — and critical — summary of a very broad and deep intellectual and theological school of thought which, while it initially launched from a single port, has now — almost because of rather than in spite of the rifts and disputes of its leaders — sailed far and wide and has carried its “Christian libertarian” message to lands more distant and in ways far different from what its founders may have originally intended or anticipated.

For those of you who embrace the biblical-theological-eschatological message of Christian Reconstruction (and even if you don’t!), this article may serve to “connect the dots” and fill in the timeline of your understanding a little bit better with “the good, the bad and the ugly” of how we got here, where we came from, where we’re going and where we stand as a movement.

If anything, it shows the human side of fallible but gifted men who have played strategic, providential roles in moving the certain advancement of the kingdom of God forward to the “next level” of integration and transformation.

My main criticism is that it portrays Rushdoony’s objective (and by extension, the objective of his colleagues) as that of founding a “theocratic America” rather than fostering a theonomic, self-governing, self-consciously biblical Christianity, both in America and around the world. And regarding Gary North, well, once you get used to his in-your-face analysis and “acrid prose,” his writing becomes music to your ears!

(Compare this with an alternate assessment (“Christian Reconstruction is alive and well”) written from a pastor’s perspective, that is more recent (and more brief), which I comment on here.)

————————————————-

The Libertarian Theocrats

By Michael J. McVicar, Fall 2007

In their struggle to understand George W. Bush, some liberal intellectuals have looked to the writings of Rousas John Rushdoony, the Armenian-American minister whose championing of a theocratic America influenced some of the nooks and crannies of the Christian Right during its rise to prominence. For example Mark Crispin Miller, in his frontal assault on George W. Bush’s response to the September 11, 2001 terrorist attacks,1 charges that Bush not only acted unconstitutionally, but in his religious imagery echoed the infiltration of Rushdoony’s ideas into his Administration (and the Republican Party at large). Miller interprets Rushdoony’s theology as a call for Christians to take “dominion” over all aspects of the federal government and replace it with a theocracy.2 “With their eyes on the future, those [Rushdoony followers] at work on forging an all-Christian USA are overjoyed that Bush is president, for they correctly see the regime’s imposition on the people as itself a signal victory for their movement.”3

But a spokesman for the think tank Rushdoony founded told me Miller is wrong (Rushdoony himself died in 2001). Registering disgust, Chris Ortiz of the Chalcedon Foundation in Vallecito, California, explained that Christian Reconstructionists, as they call themselves, think the war in Iraq is both immoral and ungodly. Not only are a good many stridently critical of the Bush administration, Ortiz said, he agreed with Miller’s indictment of Bush, which he heard during a recent radio interview. At best, some Reconstructionists might see Bush as a well-intentioned fool, Ortiz told me. Many see him as a manipulative politician who snowballed the American people into supporting his disastrous presidency.

Those casually familiar with Rushdoony and Christian Reconstruction may find Ortiz’s comments befuddling since a recent spat of popular books like Miller’s Cruel and Unusual have argued the exact opposite, identifying Rushdoony and his followers as allies of the Bush administration. Ortiz surely wants to distance himself from a failing president, but his remarks also reveal a Reconstructionist distaste for the hard, government-centered politics that brought Christian conservatives into the corridors of Beltway power.

Since the movement’s emergence in the mid-1960s, Christian Reconstruction has always been a little different from other factions of American conservatism. Not surprisingly, the movement wins attention for Rushdoony’s call for the eventual end of democracy in favor of a Christian theocracy, and his insistence that a “godly order” would enforce the death penalty for homosexuals and those who worship false idols.4 But Christian Reconstructionists insist that they have always been uncomfortable with authoritarian institutions of political power because, unlike Pat Robertson and Jerry Falwell, Rushdoony wedded his rigid theological perspective with a libertarian perspective that looked outside the boundaries of popular conservatism for answers to the problems facing the United States.

“Christian Libertarians”

At first glance, the phrase “Christian libertarian” seems a contradiction, especially when one applies it to Dominionists – as the full range of those calling for a Christian nation are called – and Christian Reconstructionists. It is true that today a secular – and in some cases rabidly atheistic – tendency dominates libertarianism. But this has not always been the case.

During the 1930s, a wide variety of business, intellectual, and religious leaders banded together to attack Roosevelt’s New Deal policies. Those who emphasized the sovereignty of the individual citizen, resistance to a centralized bureaucracy, and the benefits of unfettered free market capitalism eventually coalesced into the libertarian movement that we know today. For a brief period into the 1940s, these anti-New Deal forces formed an alliance with Protestant religious leaders determined to resist “socialistic” tendencies within the church.5 While this cooperation was short-lived, it had a profound impact on the contemporary Christian Right.

The chief target of these economically conservative evangelical clergymen was the Social Gospel, a wide-ranging theological and social movement rooted in the late 19th century whose champions sought to fight poverty and improve the conditions of America’s poorest using the government to regulate market forces. The Social Gospelers pulled together across denominational lines to advocate for a heightened awareness of labor conditions in the country. But the movement had a theological side; its clergy tended to emphasize the corporate, collective nature of salvation. Moreover, many were willing to embrace evolutionary theory as a means of explaining human origins. Such a naturalistic perspective led to a willingness to see human beings as the product of their material and social environment.

Like many in the Progressive Era, the reform-minded period before World War I, the Social Gospelers believed that legislation and government regulation could change Americans for the better by changing the social environment in which they lived. By focusing attention on the social context that drives individuals to sin, the social gospel seemed to downplay the individual, embodied experience of salvation that American evangelicals have traditionally sought.6 Not surprisingly, many prosperous American churchgoers found the emphasis on economic justice over the saving of souls to be yet another expression of the “socialistic” threat to the American way of life.

While the social gospel lost much of its impulse during the economic boom following the war, popular interest in the movement reignited during the Great Depression of the 1930s. To resist this renewed influence – and defend capitalism – the alliance between business and religious leaders sought to reemphasize individual spiritual regeneration and to downplay the effects of social constraints on individual choices.

In 1935, Rev. James Fifield of Chicago formed Mobilization for Spiritual Ideals to address these concerns. Popularly known as Spiritual Mobilization, Fifield’s operation earned the fiscal support of such right-wing philanthropists as J. Howard Pew of Sun Oil, Jasper Crane of DuPont, and B.E. Hutchinson of Chrysler. Facing the daunting task of resisting nearly five decades of entrenched liberal Protestant teaching and the harsh reality of the Depression, Fifield recruited preachers and laymen eager to resist the massive redistribution of wealth envisioned by President Roosevelt. His appeal was simplistic but effective. American clergymen needed to start preaching the Eighth Commandment: “Thou shalt not steal.” In this, the shortest commandment, Fifield and his followers believed they had found the biblical basis for private property and a limit to the government’s ability to redistribute wealth, tax, and otherwise impede commerce.7

In order to undermine government-sponsored economic redistribution, the ministers and laymen Fifield hired focused on the spiritual causes of poverty rather than the social concerns of the Social Gospelers. The New Deal and the conflicts with the Nazis and Soviets were manifestations of humankind’s rejection of God’s divinity for that of a centralized bureaucracy. An all-powerful bureaucracy, they warned, usurped the “Christian principle of love” with the “collectivist principle of compulsion.”8 Beginning in 1949, the Christ-centered free market ideals of Spiritual Mobilization reached nearly fifty thousand pastors and ministers via the organization’s publication, Faith and Freedom.9 With the rhetorical flare of such libertarian luminaries as the Congregationalist minister Edmund A. Opitz, the Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises, and the anarchist Murray Rothbard, Faith and Freedom moved many clergymen to embrace its anti-tax, non-interventionist, anti-statist economic model.

In his Faith and Freedom articles, Opitz formulated a systematic theology in support of capitalism, merging economic responsibility with individual salvation to form a “libertarian theology of freedom.”10 In assessing the threat of communism and fascism, Opitz argued that the solution was not collective political action. Instead, he noted that the “crisis is in man himself, in each individual regardless of his occupation, education, or nationality.”11Jesus’ Good News was that “the Kingdom of God is within you,” making every man’s salvation an internalized, personal matter. In Opitz’s reading, Jesus’ gospel becomes the basis for a radical individualism that “was the foundation upon which this [American] republic was established.”12

By the mid-1950s, prominent secular libertarian organizations like the Foundation for Economic Education (FEE) and the Intercollegiate Society of Individualists (ISI) began to supplant Spiritual Mobilization’s influence in libertarian circles. In fact, many of Faith and Freedom‘s regular contributors like Opitz and Rothbard13 left Spiritual Mobilization and began writing for FEE’s publication, The Freeman. Further, Ayn Rand’s atheistic Objectivism pulled many libertarians away from the Christian ideals of Spiritual Mobilization.

While secular libertarianism triumphed, the remnants of its Christian heritage persisted among a small cadre of thinkers and activists who were reluctant to completely jettison Christ from the economy. Spiritual Mobilization helped a generation of theologically and economically conservative clergy find an alternative to the Social Gospel, New Deal, and communism that resonated with their traditional values, pro-business sympathies, and Christian faith. Faith and Freedom encouraged clergymen to see government as a problem, not a solution. The solution wasn’t to take over the government; it was to replace it with something radically different.

The Libertarian Theology of R. J. Rushdoony

Among the many ministers who read Faith and Freedom was a young Presbyterian pastor living in Santa Cruz, California, named R. J. Rushdoony. Rushdoony was attracted to Faith and Freedom‘s consistent warnings of the dangers of a centralized governmental bureaucracy. Born in New York City in 1916 to survivors of the Armenian Genocide, Rushdoony knew the dangers of centralized power all too well. Just a year before his birth in the States, Rushdoony’s older brother Rousas George died during the Ottoman Siege of Van, becoming one of 1.5 million Armenians eventually killed byTurkish forces.14 Rushdoony’s father Y. K. Rushdoony secured his family’s escape first to Russia and eventually to New York City.

Beyond the dangers of governmental violence, Rushdoony was also particularly attracted to Faith and Freedom‘s articles on public education.15 Like many conservative clergymen, Rushdoony saw public schools as hotbeds for collectivist indoctrination and anti-Christian pluralism. Faith and Freedom suggested that it was just to resist compulsory public education, but Rushdoony found the publication’s writers to be inadequate theologians. Therefore, during the 1950s Rushdoony set about to provide a systematic theological justification for Christians to reject public education and embrace locally organized, independent Christian schools. Deploying a unique blend of libertarianism with the most rigorous Calvinistic theology he could muster, Rushdoony delivered a series of lectures on Christian education. When Rushdoony collected the lectures into a single volume, Intellectual Schizophrenia, Edmund Optiz wrote an enthusiastic foreword and helped to secure Rushdoony’s position as a rising star in the Christian libertarian movement.

It is important to understand Rushdoony’s critique of public education, because it is a microcosm of his broader theological project. As a theologian Rushdoony saw human beings as primarily religious creatures bound to God, not as rational autonomous thinkers. While this may seem an esoteric theological point, it isn’t. All of Rushdoony’s influence on the Christian Right stems from this single, essential fact. Many critics of Christian Reconstructionism assume that Rushdoony’s unique contribution to the Christian Right was his focus on theocracy. In fact, Rushdoony’s primary innovation was his single-minded effort to popularize a pre-Enlightenment, medieval view of a God-centered world. By de-emphasizing humanity’s ability to reason independently of God, Rushdoony attacked the assumptions most of us uncritically accept.

Following the lead of the Reformed theologians Herman Dooyeweerd and Cornelius Van Til,16 Rushdoony argued that all human knowledge is invalid if it is not rooted in the Bible. In his first book, By What Standard, published in 1958, Rushdoony summarized the ideas of Van Til and Dooyeweerd. Van Til, a Reformed Presbyterian teaching at Westminster Theological Seminary in Philadelphia, offered a radical critique of all human knowledge, arguing that it emerges from one’s theological presumptions (e.g. there is one God, many gods, or no god). For Christians, that means a three-in-one Christian God is the source of reliable human knowledge.

The implications of Van Til’s thought are far reaching. As Rushdoony explains, mankind’s first sin was an ethical fact with consequences for the nature of knowledge: when Eve succumbed to the Serpent’s temptation to “be as gods, knowing good from evil,” she asserted her own intellectual autonomy over that of God’s.17 Mankind’s “fall” into sin was precipitated by a desire to reason independently from God’s authority.18 Rushdoony extended Van Til’s ideas to their logical end to argue that all non-Christian knowledge is sinful, invalid nonsense. The only valid knowledge that non-Christians possess is “stolen” from “Christian-theistic” sources.19

In Rushdoony’s thought, knowledge becomes a matter of disputed sovereignty. Every thought that does not begin with God and the Bible is rebellious: “Man seeks to think creatively rather than think God’s thoughts after Him. Evil is the result of man’s rebellion against God…. Man’s fall was his attempt to become the original interpreter rather than the re-interpreter, to be the ultimate instead of the proximate source of knowledge.”20 Accordingly, humanity’s pretence to independent knowledge becomes a matter of rebellion against God’s Kingdom because “any attempt to know and control the future outside of God is to set up another god in contempt of the LORD.”21 Rushdoony made thinking an explicitly religious activity, a shift in focus with political implications: thinking becomes a matter of kingship, power, rebellion, and, in the final analysis, warfare. Either human thought recognizes God’s sovereignty, or it doesn’t. There is no middle ground, no compromise. It is a war between those who, like Rushdoony, think God’s thoughts after Him and those who do not.

If thinking and education are a matter of God’s disputed sovereignty, then Rushdoony believed that Christians who turned their children over to public schools were in open rebellion against God. In Rushdoony’s view, court orders forcing public schools to cease prayer and bible readings actually removed the only possible foundation for viable knowledge. Following such earlier Presbyterian luminaries as A.A. Hodge (1823-1886) and J. Gresham Machen (1881-1937), Rushdoony’s solution was to remove one’s children from public schools and to educate them in an explicitly Christian environment. Such an action brings both child and parent into accord with the “fundamental task of Christian education,” which, Rushdoony summarized, is to exercise dominion, “subduing the earth agriculturally, scientifically, culturally, artistically, in every way asserting the crown rights of King Jesus in every realm of life.”22

In many of the Faith and Freedom articles published during the 1940s and 1950s, Rushdoony saw a reservoir of popular discontent with compulsory public education and he hoped to develop it as an explicitly Christian resistance to the authority of centralized political structures. In this sense, Rushdoony was a shepherd in search of a flock and the libertarians looked more promising than alternatives. When Edmund Opitz helped secure Rushdoony a position with a small but influential libertarian organization known as the Volker Fund in 1962, Rushdoony moved to exert his unique brand of Calvinist-inspired libertarianism on the organization. He began writing a host of position papers that attacked public education, reinterpreted American history in starkly Christian terms (see box), and advocated for the regeneration of America along explicitly Christian lines. After some internal wrangling, the Fund fired Rushdoony in 1963, but the separation was gentle, giving Rushdoony the necessary resources to write two more books.

Rushdoony’s dismissal from the Fund reflected many of the secularizing changes in American libertarianism of that time. As libertarianism evolved into a more mainstream movement, it forced most of its religious defenders to the side. Rushdoony was but one casualty in this process. By the time he left the Fund, however, he had secured enough experience as a grant writer and public lecturer to set his own course. In 1965, he founded the Chalcedon Foundation, an educational organization that he used to popularize his call for a “Christian Reconstruction” of American society. In the process of forming Chalcedon, Rushdoony decided to mentor an ambitious college student who shared his passion for libertarian economics and Christianity. Their relationship would prove one of the most fascinating – and volatile – in the history of the Christian Right….

(This is a LONG essay! Continue reading here.)